Once a telephone network connects a city, every new subscriber makes it more valuable. That's powerful. But in a place with no phone lines you'd need to spend billions before anyone could make a single call. Meanwhile, someone puts up cell towers and connects everyone in a fraction of the time. Africa. This pattern shows up everywhere, read on.

When Your Moat Becomes Your Cage

Telecommunications

Telephone companies spent a century building copper wire networks. In wealthy countries, this was unbeatable. Everyone was connected and replicating it would cost billions.

But in developing nations mobile technology skipped the whole thing. Cell towers connected millions in years.

Kenya, India, and much of Africa never built landline networks. They went straight to mobile.

Financial Services

Banks built moats with branches everywhere and regulations, also real estate, security and tellers. Expensive to replicate.

M-Pesa in Kenya bypassed all of it. Transaction costs dropped a lot. Millions who never had bank accounts suddenly had financial services.

Energy

The electrical grid took decades and billions to build. Power plants. Transmission lines and substations. In wealthy nations, those sunk costs made it hard to switch away from coal and gas.

In places without electricity? Solar panels and batteries offered a different path. Just distributed energy installed where people lived. Clean energy from scratch, skipping fossil fuels entirely.

Automobiles

The internal combustion engine was the ultimate barrier to entry. A century of engineering made it incredibly complex. Only established manufacturers could compete.

Electric vehicles rendered that expertise irrelevant. New entrants didn't need to catch up on engine technology. China invested heavily in EVs and became global leaders without ever mastering traditional engines.

Healthcare

Healthcare required clinics, hospitals, and roads for supplies. In rural areas, no infrastructure meant no care.

Telemedicine and drone delivery changed that. Virtual consultations eliminated the need for buildings. Drones delivered blood and medicine on demand, flying over impassable roads. Results? 56% drop in maternal mortality. 60% fewer medicine stockouts. 67% less vaccine wastage.

And so many other examples, I leave you to discover about new Spanish agriculture system.

What These Moats Had in Common

Look at these examples, the same characteristics appear every time:

High capital intensity

Physical infrastructure

Centralized systems

Legacy lock-in. Sunk costs made adaptation impossible. Once you'd spent billions on coal plants or film processing, you couldn't walk away.

Geographic constraints. You needed physical presence where customers were.

Complexity. Accumulated expertise that took decades to develop. Internal combustion engines.

The vulnerability of all is, these became liabilities when new technologies dematerialized, decentralized, or simplified things. The moat became a cage.

What This Means for Building Companies

Physical assets are double-edged. They create barriers in established markets. They become anchors when the game changes. The question isn't whether your moat is strong. It's whether it stays relevant and strong.

Watch for dematerialization. When physical products become digital, economics shift dramatically capital requirements drop and speed increases. New entrants compete without matching your infrastructure.

Be honest about sunk costs. Your billion-dollar investment doesn't make it the right path. That investment might prevent you from seeing where the market's heading. Fujifilm survived by recognizing its real expertise was chemistry, applicable to cosmetics and medical imaging, not film.

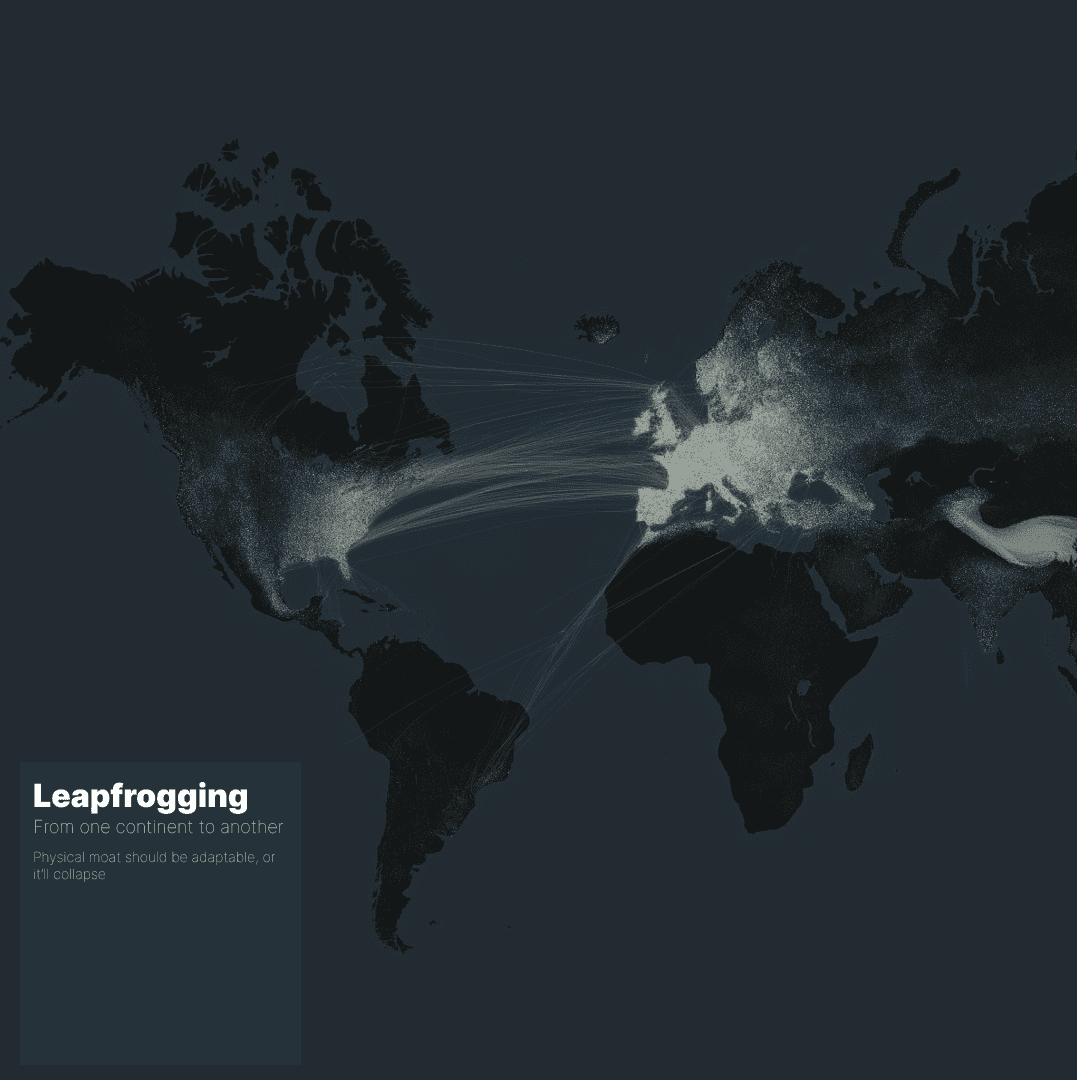

Geography matters differently now. Your dominance in established markets tells you nothing about vulnerability in new ones. Mobile didn't disrupt landlines in Manhattan. It leapfrogged them in Nairobi. EVs aren't replacing gas cars in Detroit. They're becoming default in markets still building infrastructure.

The physical network paradox reveals something fundamental: the moats that make you unbeatable today can make you irrelevant tomorrow. Not because they stop being strong.

This pattern makes sense in isolation, but hold on. What happens when we add other variables?

Time matters more than anything. Heavy physical industries are slow to change. The clock is ticking while they're locked into yesterday's infrastructure.

Meanwhile, new technologies move fast. Software updates happen overnight. Solar panels install in days. This speed advantage compounds the vulnerability of physical moats.

Harvard Business Review identified time as a critical competitive advantage back in 1988. Fast beats slow. Flexible beats rigid. The physical network paradox and the time advantage aren't competing theories. They're the same story told from different angles. When your moat is built from concrete and copper, you can't adapt quickly enough when the market shifts. Your strength becomes your cage because you're moving in slow motion while others sprint past.

References

Aker, J. C., & Mbiti, I. M. (2010). Mobile phones and economic development in Africa. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(3), 207–232. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.24.3.207

Stalk, G. (1988). Time—The next source of competitive advantage. Harvard Business Review, 66(4), 41–51. https://hbr.org/1988/07/time-the-next-source-of-competitive-advantage

Suri, T., & Jack, W. (2016). The long-run poverty and gender impacts of mobile money. Science, 354(6317), 1288–1292. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah5309